Backdrops

Cookbooks & Household Literature

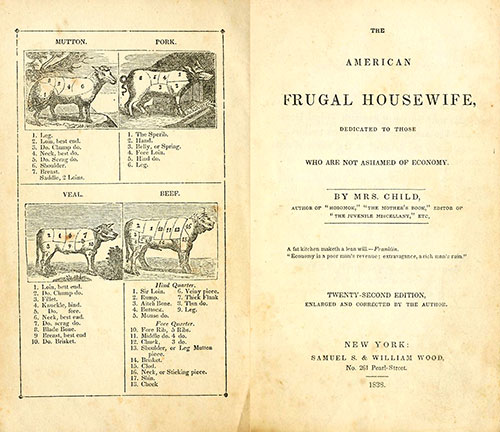

"The American Frugal Housewife," by Lydia Maria Child, was originally published in 1829. Enormously popular, it went through 30 editions in 25 years. Image courtesy of Archive.Org.

An amusing 19th century anecdote about an inexperienced young wife preparing a chowder ended with her sympathetic husband burying the sad result—raw on top, cooked in the middle and burnt to the bottom of the pot—in the yard under cover of darkness. Readers may have laughed or winced at the tale, which summed up the hopes and fears of a newly wed couple beginning their new life together.

Running a household in the early 19th century required strength, stamina and a variety of skills. In the pre-industrial era, keeping family members fed and clothed in a tidy house required a level of labor and commitment that kept many women working before the sun rose until they fell into bed at night. For women who lived on farms (as most people did in this period), their workload included milking cows, making butter and cheese, butchering and processing meat, and making candles and soap, as well as maintaining and harvesting fruits, vegetables and herbs from the kitchen garden. Child care was part of the daily rhythm of life and most married women bore between five and seven children.

Women were expected to train children from an early age to perform household chores. Young girls began learning to sew as young as three, and learned from their mothers how to prepare food and tend the hearth and fire the bake oven and the myriad other tasks of running a household. If the story of the ill-fated chowder is any indication, not every young woman entered the married state possessed of all of the necessary skills the role required. Luckily, by 1829, novices and the more experienced could consult what rapidly became one of the most popular advice books of the century: The American Frugal Housewife. Its author, Lydia Maria Child, knew firsthand what it was like to try to make ends meet while maintaining the lifestyle expected of respectable, middling Americans in the 1820's and ‘30's. Child and her husband were living in Boston and struggling financially when she organized a lifetime’s experience of making do into a volume that would go through over thirty editions within 25 years. The couple moved to Northampton in 1838, where they became strong antislavery advocates, a controversial stance that eventually cost Child much of her commercial success.

The subtitle of her text, Dedicated to those who are not afraid of Economy, signaled that this was to be a book focused on low-cost solutions for daily living on modest means. For those interested in recipes and strategies requiring more expensive foods and household goods, Child rather severely directed them to Eliza Leslie’s Seventy-Five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats, published in the same period. The Hitchcocks preferred plain fare and as a minister’s wife, Orra likely would have appreciated Child’s frugality.

As society placed increasing weight on child-rearing and the domestic sphere as a refuge from a hurly burly world, women like Orra Hitchcock increasingly turned to Child and other advice book writers for suggestions and inspiration. In addition to her Frugal Housewife, Child also wrote The Mother’s Book. Religious and secular periodicals were another source of comfort, advice and, in the case of Godey’s Lady's Book, a chance to enjoy lighter offerings devoted to fashion and entertainment. Edited by Sarah Josepha Hale from 1830-1877, Godey’s included poetry, interesting articles, and engravings. Contributors included Edgar Allen Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Washington Irving, and Frances Hodgson Burnett. Each monthly issue contained an eagerly anticipated, hand-tinted fashion plate that communicated the latest women's fashions. Later issues included patterns for home sewing and a piece of sheet music.

Hale’s formula was a tremendous success, and circulation increased dramatically despite a rather higher-than-usual annual subscription fee of three dollars. Godey’s became a household word by the mid-19th century and its editor used the magazine to tirelessly advocate for women’s education and the opening of professions that traditionally excluded them, such as medicine. The overarching theme was a combined celebration of women and domesticity. Not surprisingly, it was in the pages of Godey’s that Hale campaigned for a national Thanksgiving holiday.

As a woman of science married to a scientist, Orra Hitchcock may have especially appreciated the scientific aspects of domestic economy in Catherine Beecher’s A Treatise on Domestic Economy for the Use of Young Ladies at Home and at School, first published in 1841. Like many female intellectuals and reformers of the era, Beecher believed that women were natural teachers and nurturers of the young. Through sharing “receipts” (recipes), latest fashions, affecting prose and poetry, and child-rearing advice, cookbooks and household advice literature sought throughout the 19th century to support and elevate women as they fulfilled what society considered their essential role as mothers in a rising republic.

Dig Deeper

- Orra White Hitchcock

- Edward's Love Note to Orra Suggesting a Tryst

- Orra White's Gown

- Emilie Hitchcock’s Letter to Edward Hitchcock May 19, 1819

- Edward's 1821 Love Poem for Orra

- Orra White's Letter to Lucy Fowler, February 19, 1820

- The Hitchcocks' Piano

- Edward's Love Note to Orra Wishing for Bad Weather