Backdrops

The Lyceum Movement

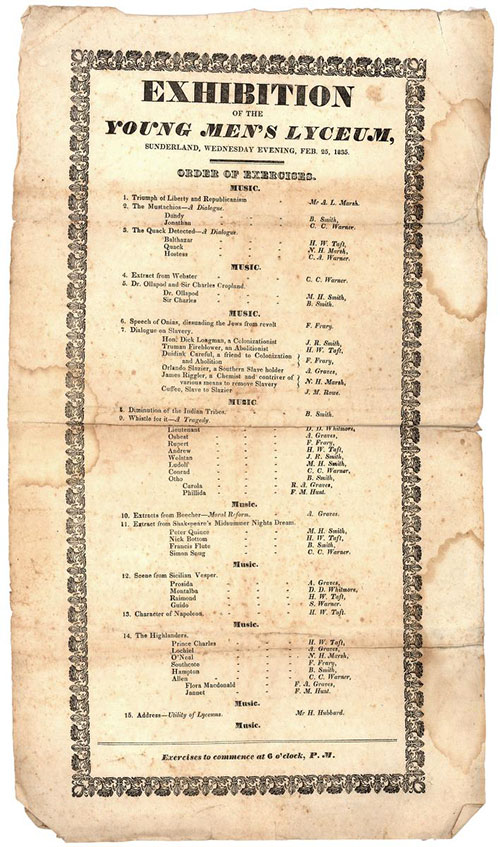

Sunderland is next to Edward Hitchcock's childhood hometown of Deerfield, Massachusetts. This calendar is typical of what could be expected at a night at a lyceum. Image courtesy of Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library.

In the decades following the American Revolution, men and women turned their energy and attention to creating a society that reflected the ideals and beliefs of the new republic. Believing that active, well-informed citizens were the bedrock of a free government and society, Americans were keenly interested in education. Ordinary people, who before the Revolution would not have looked beyond the village school, now sought expanded curricula and broader cultural horizons for their children.

This drive for greater knowledge did not stop with the rising generation. To borrow a phrase much in use today, many 19th-century adult Americans were becoming “life-long learners.” An ever-growing number of periodicals, journals and newspapers fed what seemed an insatiable appetite for information on every conceivable subject, from political philosophy to history to science and technology. Already accustomed to lengthy public addresses and sermons, men and women eagerly welcomed traveling lecturers who obligingly lectured and demonstrated on myriad topics, ranging from the principles of electricity to lively presentations on exotic animal species and habitats.

In this way, adult Americans became avid consumers of what were known in the 1830s as "lyceums", or "lyceum lectures". Named after the famous school in ancient Greece founded by Aristotle, the word lyceum matched perfectly the craze for all things neoclassical in this era. (The fascination with ancient Greece was not confined to the United States; Napoleon Bonaparte adopted the word “Lycée” for French secondary schools in 1802.)

By the 1830s, Lyceum societies were popping up across the country, including rural New England towns. Organizers brought in guest lecturers, organized debates and even theatricals. In Sunderland, Massachusetts, the best remembered lyceums were hosted by the Union Club formed in 1835. A town history later recalled how an ambitious young man “was in the habit of walking to the village to attend the weekly lyceum, an institution which has done much for education in many a New England town.”

In nearby Deerfield, Massachusetts, the brick schoolhouse in the center of the village hosted lyceums in a hall on its second floor. Town resident Jonathan Ashley Saxton was a frequent local speaker. An abbreviated list of the talks he delivered between 1832 and 1850, is typical of lyceum lectures in this period: “An Ode to [George] Washington” (1832); “a Lecture relating to the First Continental Congress,” 1837; “Women’s Rights” (1838); “Freedom of the Slave in Antigua” (1838); “Would God, that all the Lord’s People were Prophets” (1840); “The Temperance Movement” (1841); “How Much Land and Property, and I have None!” (1844); “Inequalities of the Human Condition” (1849); “Resolved that the Militia System ought to be Abolished” (1850).

Ashley and other speakers did not shy away from controversial, contemporary social and political issues. On a Thursday evening in 1851, guest speaker William G. Bates addressed a Greenfield, Massachusetts, lyceum on the question, “Ought Foreign immigration to this country to be encouraged?” As much entertainment as a serious quest for knowledge, lyceums offered men and women from all walks of life the the chance to encounter new ideas in a community setting.