Backdrops

Mail and the Post Office

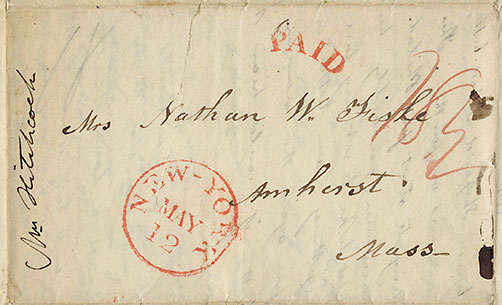

Street addresses were not yet in use, as people picked up their mail from the post office or other local mail center. Image courtesy of Edward and Orra White Hitchcock Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

Well into the 1800s, people separated by distance relied on handwritten letters and printed materials to communicate. High levels of literacy enabled Americans from all walks of life to read correspondence and the latest news. An exception were enslaved African Americans in the Southern states, where hostile slave holders and special legislation forbade teaching reading or writing to slaves. Even here, unknown numbers of determined African American men and women defied the odds by learning to read and write despite great personal risk.

Once a piece of mail was addressed with the name of recipients and the town and state in which he or she lived, the sender needed to decide how to deliver it. If they knew someone going to the town where the recipient lived, a letter writer could ask that person to carry it along and deliver it; many letters and packages arrived in this way. Otherwise, the letter would have to travel by United States mail.

The population of the United States grew exponentially in the decades following the Revolution, but the number of letters and printed material sent through the mail, especially newspapers, increased even more dramatically. Between 1790 and 1830, the volume of letters sent through the United States postal service increased over 300% and newspapers over 200%. In 1800, there were 903 post offices; only fifteen years later, there were more than 3,000. During these same decades, mail began traveling more and more quickly along new post roads, canals, railroads, steamboats, and, by the 1840s, transatlantic steamships.

Mailing a letter required taking it to the nearest post office and telling the postmaster where the letter was bound. Not every town had a post office but larger towns and cities did; the postmaster often worked out of a tavern in the town center where the stagecoach stopped. Unless they specifically asked to prepay, senders did not pay postage for delivery within the United States; the recipient was expected to pay on receipt at a base rate of ten cents per page. (If the letter was to someone overseas, the sender had to pay the postage to mail it to the nearest seaport post office, where it would be sent via ship; the recipient would have to pay any additional foreign postage.) In all cases, the postmaster wrote or stamped the postage on the letter and set it aside ready to be sent on the next mail stage, where it would travel locked in an official postal box with the other letters, newspapers and magazines. Postage rates for letters was high, in contrast for much lower rates for newspapers. Higher rates for correspondence essentially helped subsidize circulation of hundreds of newspapers. By 1810, Americans were buying twenty-two million copies a year and three million of these were being carried by the postal service.

It was up to the recipient to go to the nearest postmaster to see if he or she had received any mail. The postmaster would produce the letter and require payment of the postage. For nearby towns with regular mail service, deliveries generally would arrive within a day or two of being mailed. In contrast, it could take several days or even weeks for letters or newspapers mailed to states outside New England, or overseas to arrive at their destination.

In the 1830s, letters, newspapers and magazines were carried in stagecoaches, canal boats and sailing ships. By the 1840s, railroads began connecting inland New England towns to larger towns and port cities. Edward Hitchcock's article published in the American Journal of Science on the region's exciting fossil finds would have traveled to England on a fast sailing vessel called a packet ship, arriving in about 18 days if wind and weather cooperated. Within a few years, however, steamships would routinely take just two weeks to travel to Western Europe. Advances in transportation technology and a growing network of roads and rails thus helped to collapse the distance between far-flung family, acquaintances, business partners and colleagues, enabling the swifter spread of information and discussion about new inventions and discoveries among scientists and interested members of the public on both sides of the Atlantic.