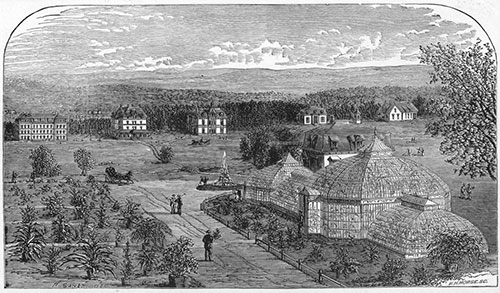

Campus Views, 19th Century, 1860s-70s, undated. University Photograph Collection (RG 110-176). Image courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

Farming was the main occupation of most Americans in the early 19th century and agriculture was one of the most vibrant fields for technological innovation in the new nation. Promoting agriculture was considered an essential component of the mission of the United States patent office when it was created in 1790. The majority of early patents were devoted to improvements, from the cotton gin to more efficient shovels, plows, and threshing machines.

The Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture was founded in 1792. Its first trustees and members included John Adams, John Hancock and other leading men of the Commonwealth; their example encouraged other well-to-do farmers to begin experimenting with new techniques and scientific approaches that complemented, and in some cases, displaced traditional farming methods and customs that had been passed down through generations. New publications like Thomas Fessenden’s New England Farmer shared these and other new ideas about anything and everything to do with agriculture.

In 1813, a group of scientifically-minded Deerfield farmers established the Franklin Association. Members gathered a library of leading agricultural publications and met quarterly with the goal of “improvement in the whole management and economy of the farm with all its appurtenances." A similar association promoted “The improvement in the management and economy of a farm: promotion of domestic manufactures, and researches into the natural history of our county, in the vegetable, animal, and mineral kingdoms, so far as they are connected with agriculture.” John Wilson was a progressive farmer active in the Franklin Association. The changing composition and expansion of his apple orchards throughout the 1820's, reflected his participation in the post-Revolutionary War wave of agricultural improvement. Wilson began extensively documenting his orchards, noting the types of apples he planted, when he planted them, and his methods of cultivating them, including the scientific practice of grafting.

This intense focus on scientific farming resulted in more intense, efficient cultivation and animal husbandry. For example, the new iron mouldboard plow in the early 1800's enabled farmers to till more deeply with less draught, or pull by oxen, enabling them to plow more acreage and rotate crops more efficiently while employing less labor—all important developments as farmers sought to increase productivity to take advantage of expanding markets. Wilson was among those who submitted patent designs for new, more efficient plow designs. In 1833, Solomon Williams of Deerfield offered a testimonial for a new cast iron plow developed by Colonel John Wilson of Deerfield. Williams had “no hesitancy” in endorsing Wilson’s plow after three full seasons of use, saying he considered it “vastly superior of any Plough he has ever used in a course of nearly fifty Years.”

Inventors also improved existing hand tools. In 1831, Amasa Goodyear patented the spring steel manure and hay fork. The lighter-weight construction with steel tines was a huge improvement over the earlier cast-iron implements in common use during the 18th century. Three years later, Silas Lamson of Greenfield, Massachusetts, patented the curved snath, the body to which a scythe blade is attached for mowing hay. Anyone who has raked leaves and hurt their back can understand the revolutionary impact of this ergonomic improvement and it became the standard design for snaths, an essential tool for haymaking. The success of Lamson’s invention funded the startup of an extremely successful cutlery factory in Shelburne Falls-the Lamson Goodnow Company, founded in 1837, one of the oldest cutlery companies in the US and still in operation.

Agricultural societies, lending libraries, almanacs and periodicals all encouraged farmers to improve techniques and try new methods. While not all farmers readily adopted these new ideas, agricultural reformers enjoyed far greater success when they created a vehicle to bring farmers together and highlight innovative and high-performing agricultural practices: the regional fair. Fair organizers rewarded those who produced top-of-the-line livestock and crops with prizes and publicity. The Berkshire County Fair, organized in 1811, was the first of its kind in Massachusetts, but others soon followed, including the Franklin County Fair, founded in 1848, by the Franklin County Agricultural Society. Fairs were enormously popular and quickly became an agrarian institution throughout the country.

Despite these efforts, Americans lagged behind Great Britain in establishing formal schools devoted to teaching the principles of scientific agriculture. In the 1850's, Massachusetts began considering founding a state agricultural school, possibly in Amherst. With this in mind, Amherst College asked its president, Edward Hitchcock, to gather information while traveling abroad about European institutions for agricultural education such as the Agricultural Training School at Hoddesdon in Cambridge, England. Upon his return, Hitchcock quickly wrote a report to the state and gave talks encouraging those active in the state’s agricultural societies to call upon the legislature to establish a school. In a speech to members of the Norfolk, Massachusetts, Agricultural Society, Hitchcock assured his listeners that “you will have schools when you ask for them with earnestness and continuity.” He claimed for agriculture “a high rank on scientific grounds.” He pointed out that farmers “in fact engaged in the prosecution of some of the most complicated & difficult experiments in the whole circle of science”, requiring “a skillful application of . . . Chemistry, of Physiology, of Botany, of Zoology, of Meteorology, of Geology.”

Ten years after Hitchcock's address to the Norfolk Agricultural Society, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act. The 1862 Act granted each state 30,000 acres of land for each of its congressional seats to finance the establishment of colleges specializing in “agriculture and the mechanic arts.” In 1863, Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew signed the charter creating the Massachusetts Agricultural College. The college opened its doors in 1867, with four faculty and 34 students, and charged $36 for tuition. It became the Massachusetts State College in 1931, and the University of Massachusetts in 1947.