Backdrops

Mastodon Bones and Other Fossils in America

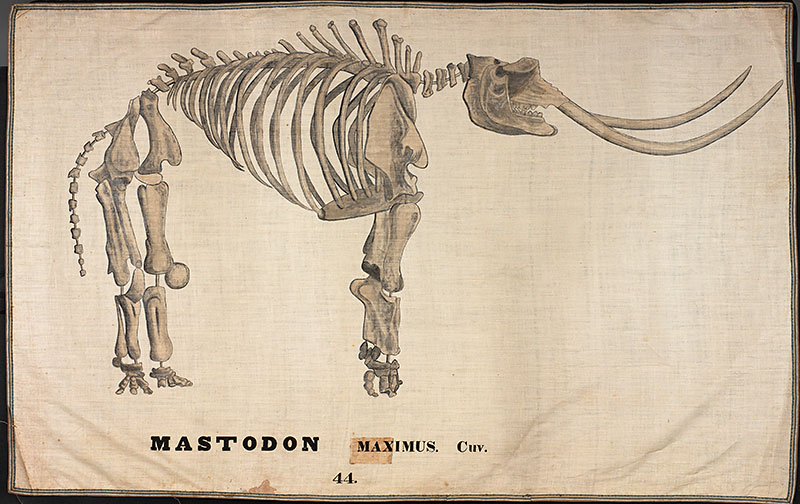

Image courtesy of Edward and Orra White Hitchcock Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

Americans in the first half of the 19th century were well aware of fossils. As early as 1705, a fossilized five-pound mastodon tooth was found in Claverack, New York, about 90 miles west as the crow flies from Edward Hitchcock's hometown of Deerfield, Massachusetts. Some considered it to be proof that giants had lived on the North American continent before the days of the flood described in Genesis. The beast whose tooth it had been was called incognitum, meaning the unknown.

Nearly a century before Edward Hitchcock's birth in 1793, the Reverend Edward Taylor, in Westfield, Massachusetts, wrote a poem about the creature whose bones were found near the tooth. Judging from their size, Taylor calculated the animal to have been 60 to 70 feet high (rather than a more realistic 10 feet). Taylor's friend, Cotton Mather, popularly known today chiefly in association with the Salem witch trials, ascribed the bones to two-legged giant humans rather than four-legged elephant-like animals. The idea of giants confirmed his belief in the perfect and literal truth of Scripture, which refers to giants in Genesis. Since he was not an anatomist, he did not know the difference between human and other mammal bones.

Over the years, more mastodon remains turned up in South Carolina, where slaves noticed the resemblance to elephant bones; in Bone Lick, Kentucky; in the Niagara Falls area; and Missouri. Today, they have been found across the country, most recently underwater in Florida.

Mastodon discoveries in America played a role in persuading geologists and, eventually, a larger public, of the reality that a species could become extinct. In Paris, the great comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier was collecting specimens and developing the techniques that made it possible to reconstruct these and other large quadrupeds and to demonstrate the anatomical differences between them and the living mammals they may have resembled. In the 1790's, Cuvier concluded that the incognitum, which he renamed mastodon, was distinct from mammoths and modern elephants. He argued that he and his contemporaries knew the globe well enough to be reasonably certain that these large quadrupeds no longer lived. Cuvier and a growing number of other geologists saw this as the first truly compelling evidence for the reality of extinction. The exploration of other discoveries, including those of giant ground sloths in Argentina and of giant marine lizards in France and England, soon suggested that entire faunas have changed repeatedly in geological history.