Image courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Libraries.

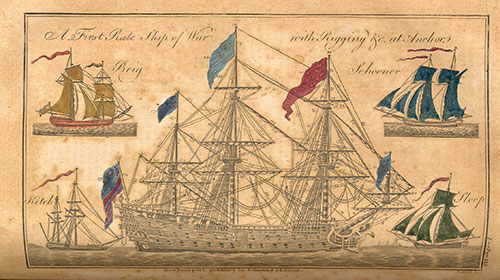

The “challenge” of Edmund Blunt gave Edward Hitchcock his first experience in public controversy over scientific credit. As a nautical publisher in New York, Blunt produced the annual American Nautical Almanac, which was based on an English version. In the book's charts of astronomical calculations, accuracy was crucial to the lives and well-being of the sea-going sailors who relied on them for navigation.

In the preface to each annual edition, he confidently included a “challenge” offering of $10.00 per mistake to anyone who could find one. It probably did not occur to him that an industrious astronomy buff in a small town in western Massachusetts would see this as easy money and take him up on it, for Edward Hitchcock was familiar with the book from his time charting the Comet of 1811. Hitchcock quickly came up with a list of 40 mistakes, which he sent in a letter to Mr. Blunt. Not pleased, Blunt sent a dismissive and belated reply. This irritated Hitchcock, who immediately came up with a list of further mistakes for 1815, ’16, ’17, and ’18.

This time, he sent his list to the American Monthly and Critical Review, also published in New York. “I wish them to be made public,” Hitchcock wrote in his letter to the Monthly, “not from a disposition to injure any individual concerned in that work, but from a sense of duty . . ." He congratulated Blunt for having made corrections to the 1819 edition, but his tone shows that Hitchcock had already mastered the art of the gentlemanly put-down:

“To the matter of his communication in your Magazine for January last, . . . any one who examines it, will perceive that it is but an unwilling acknowledgement of most of the errors I had pointed out. . . . The manner of Mr. Blunt’s communication is such as not to deserve a reply. By writing with so much warmth, he defeats his own object. As to my statements . . . whenever I may chance to notice any errors of magnitude in a work of such vital importance as the Nautical Almanac, I shall consider myself bound to offer them for publication, whether they be made by A, B, or C.”

Blunt’s reply in the same magazine thanked Hitchcock for the corrections, but defended himself on the grounds that the errors had been carried over from the English edition on which he based his work, innocently assuming that its figures were correct. This claim can be corroborated by a letter in the Philosophical Magazine, published in London, in which a letter-writer points out numerous errors in the English almanac and suggests ways to overcome problems of accuracy. As the brief announcement in American Monthly put it, “A correspondent of the Philosophical Magazine complains loudly of the omissions and erroneous figures and calculations in the Nautical Alamanck. He points out more than 40 considerable errors in the Almanack for 1819.”

Thus, Blunt was perhaps not entirely to blame, but he was unable to resist sarcasm: “I have the English Nautical Almanac for 1820, now in the hands of two gentlemen, celebrated for their mathematical science, and when finished by them, will thank Mr. H. to amuse himself in going over the pages; after which, I will publish the work, and if a deviation is made from copy, of one figure, then I will acknowledge the confidence so liberally experienced by me, to be misplaced, and at once resign the pleasure I have twenty years experienced, of publishing nautical works (which of all others, should be entirely free from error) to other hands. Till then, Mr. H. will be pleased to continue his labours, and contribute all in his power to that perfection which guides the mariner through the pathless ocean, and relieves the solicitude of a respectable class of society, which it is a duty incumbent on every man to aid.”

Edward Hitchcock never received, nor forgot, the promised $10.00 per error.