MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

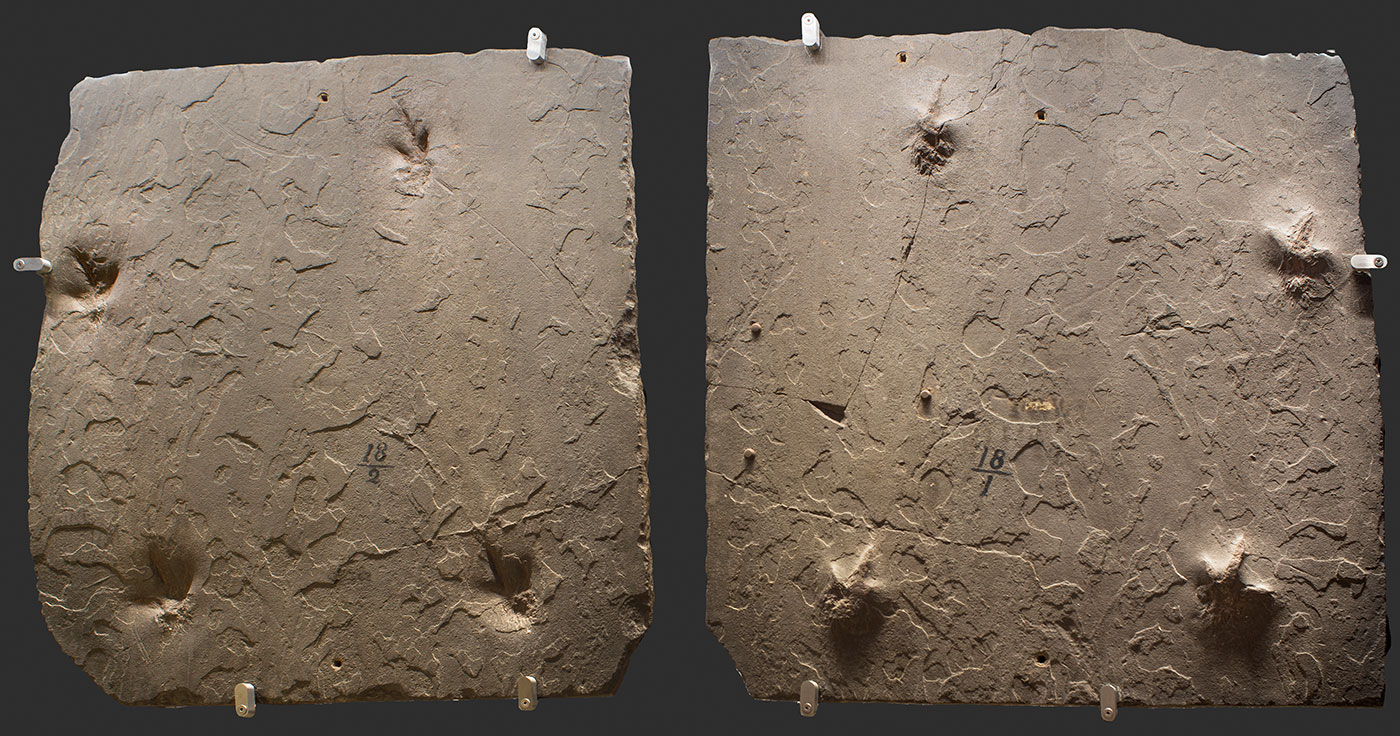

The fossils that Dexter Marsh discovered while laying sidewalk slabs in Greenfield, Massachusetts, in early March 1835. These slabs can been seen today at the Beneski Museum of Natural History on the campus of Amherst College. Image courtesy of Beneski Museum of Natural History at Amherst College.

The first tracks Professor Hitchcock learned of were in the town of Greenfield, Massachusetts. In 1835, a little over 30 years after Pliny Moody found his "Noah's raven" footprints, a laborer named Dexter Marsh noticed similar marks while splitting rock slabs to make a sidewalk in the middle of town.

Marsh had never heard of Moody's discovery—the news had not traveled the 30 miles from South Hadley—so he was surprised and intrigued by what he saw. Telling the story years later, Hitchcock said that a supervisor, Mr. Wilson, told Marsh to set the slabs aside, but from what we know of him, Dexter Marsh needed no such instruction. Although he had little formal education, he was an extremely curious, observant man who continued to give a great deal of attention to fossil footprints for many years after seeing these.

A young doctor named James Deane lived around the corner. Maybe he was just passing by, or perhaps he heard the news and strolled over to see what his neighbor had found. However it came about, when Mr. Marsh showed him the “bird tracks,” Dr. Deane’s response was markedly different from that of the Moody family.

He did not use the slab as a doorstep or speculate about Noah’s Ark and the raven. Instead, he wrote letters to two prominent scientists, one being Hitchcock and the other, Benjamin Silliman at Yale College. He described the footprints and explained why he thought the marks had been made in soft sediments by birds “thousands of years” earlier: they were shaped like bird tracks and showed a left-right walking progression.

Dr. Deane had to wait more than two anxious weeks to see what the geological experts had to say.