MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

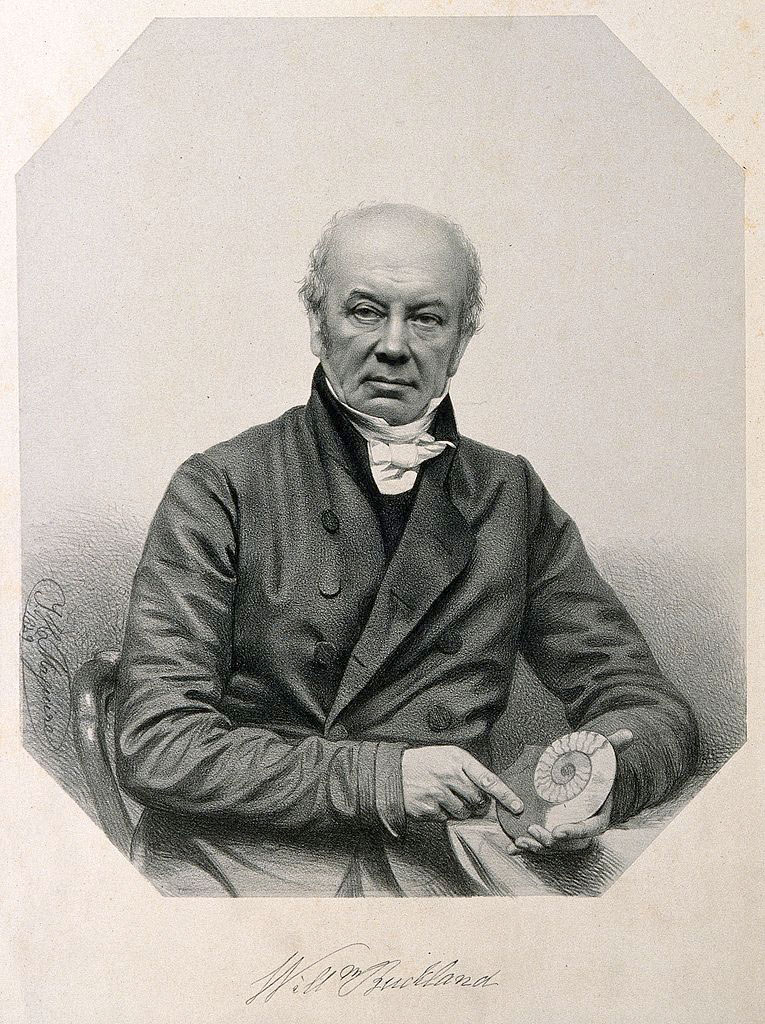

William Buckland circa 1845. Buckland believed in Hitchcock’s theory of the tracks’ origin at a time when many other scientists remained skeptical. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Hitchcock was perhaps disappointed but not really surprised when, despite his painstaking descriptions, cautious theorizing, and remarkable illustrations, the response to his revelations was skeptical.

Among British geologists, only two were convinced. Fortunately, one of them was an important geologist from Oxford University, William Buckland, who was also a cleric, so he had credibility with religious leaders as well as with scientists. Buckland moved quickly to include the tracks in the upcoming contribution he was preparing for the Bridgewater Treatises, a multi-author series of works devoted to showing how the sciences aligned with Christian views of Creation.

But the rest of the gentleman of the Geological Society of London had great doubts. Now, if Hitchcock could just find the bones of one of the enormous birds who had made the tracks—one footmark was 17 inches long!—that would be compelling evidence. The pictures in the journal were impressive indeed, but to rest such bold assertions on a few indentations in stone was taking the evidence too far.

Closer to home, an amateur geologist from Connecticut ridiculed Hitchcock in The Knickerbocker, a literary magazine from New York. Protected by anonymity, the author chided the Amherst professor for his “extravagancies” and “haste in writing” and opined that perhaps critics had indulged Hitchcock too much over the years, due to his humble origins.

Edward was not to be intimidated. He defended himself and his ideas in a following issue of the magazine, and was given a disdainful public reply in October. Silliman eventually tracked down the anonymous writer, calling him a coward and defending Hitchcock vigorously.