Impressions from a Lost World: The Discovery of Dinosaur Footprints

From Cabinets to Museums

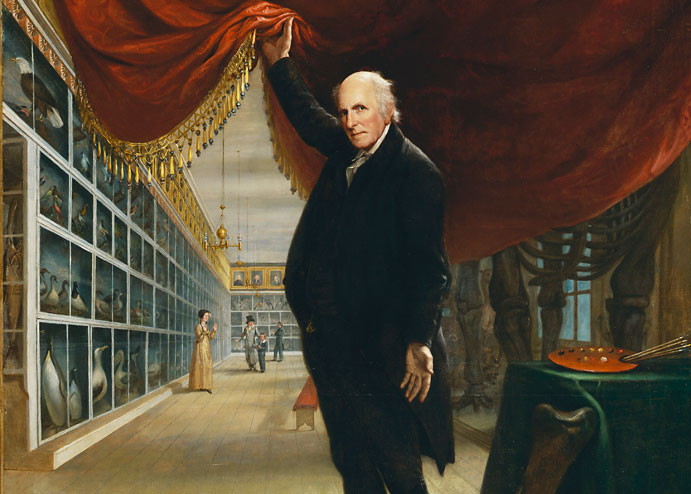

The Artist in His Museum, Charles Willson Peale Image courtesy of Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. Gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison (The Joseph Harrison, Jr. Collection).

The scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries in mathematics, astronomy and physics encouraged educated Europeans to seek in the natural world a fuller understanding of the workings of the universe. Wealthy collectors avidly sought out natural history specimens, including what they considered oddities of nature. New contact with the lands and peoples of Africa, Asia, and the Americas inspired and enabled these amateur scientists to amass collections to satisfy their taste for novel and exotic objects. Displayed in private “Cabinets of Curiosities,” these early collections were the ancestors of the modern museum.

Scientific advances and voyages of discovery fueled the belief in a new Enlightenment, or “Age of Reason," in which civilization would inevitably progress through research and discovery. These same Enlightenment beliefs lay behind the American Revolution’s rejection of monarchy for an optimistic vision of a government by and for the people. The assumption that only educated and informed citizens could sustain a free government gave new urgency to making and sharing scientific discoveries.

The new American Museum that Charles Willson Peale opened in Philadelphia in 1786, was part of this determination to enlighten and educate rising generations of the New Republic. In contrast to the old elite cabinets kept by and for the well-to-do, Peale’s museum charged a nominal 25 cent admission intended to emphasize the value attached to attaining knowledge while keeping it well within the means of ordinary citizens. “Ever desirous to please and entertain the Public,” Peale hoped to inspire all Americans to elevate their thinking by sharing “the beautiful uniformity in a variety of things.”

An accomplished painter himself, Peale’s portraits of heroes of the American Revolution appeared throughout the museum, reminding American visitors of the sacrifices and triumphs of the war for independence. He organized his collection using the Linnaean system of scientific classification, and his establishment was among the first to include painted backdrops of landscapes and habitats of the specimens he exhibited. Collections were wide ranging, reflecting a general interest in all aspects of scientific and philosophical inquiry. An advertisement in the Pennsylvania Packet in 1788, enthusiastically promoted “Mr. Peale’s Museum, CONTAINING the portraits of Illustrious Personages, distinguished in the late Revolution of America, and other Paintings–Also, a Collection of preserved Beasts, Birds, Fish, Reptiles, Insects, Fossils, Minerals, Petrifactions, and other curious Objects, natural and artificial.” In an eclectic mix of the natural and the man-made, visitors could view objects as diverse as an electrical machine and, by 1802, a mastodon skeleton Peale had excavated near Newburgh, New York. Thousands flocked to his museum, which he moved with great fanfare to the Philadelphia State House (Independence Hall) in 1802. By 1815, over 40,000 people visited each year.

Interest in collections like Peale’s was widespread. When his museum went out of business in the 1840s, P.T. Barnum and Moses Kimball eagerly purchased items from its collection for their own museums and traveling exhibits. These budding entrepreneurs fed the American appetite for the exotic and exciting with exhibits, shows and collections that included the fanciful (a "curiosity supposed to be a mermaid”) as well as elements of ancient Greek sculpture and paintings by such well-known artists as John Singleton Copley. Numerous specimens exhibited by Kimball at the Boston Museum he opened in 1841, would eventually make their way to the Boston Society of Natural History and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Still frequently referred to as “cabinets,” private collections in the early 1800s showcased a family’s cosmopolitan tastes, knowledge, and intellectual curiosity. In this same period, academies, libraries, and colleges also amassed collections intended to enlighten, engage, and educate. Beginning in 1766, Harvard College gathered, over a 50-year period, mineral, botanical and zoological specimens as well as paintings, and engravings. By the 1820s, Harvard's cabinet took up three rooms and also included scientific instruments, Native American objects and artifacts from the ancient world. When Deerfield Academy opened in 1799, it had a natural history museum containing shells and minerals, as well as such curiosities as “a bell from a Nubian dancer” and a “Turkish shoe." For Dexter Marsh, the line between a private cabinet and a public museum blurred when he decided to open a museum of fossil and geological specimens in his Greenfield, Massachusetts, home in 1847. Perhaps inspired by Dr. Gideon Mantell’s famous museum in Brighton, Massachusetts, Marsh invited all interested members of the public to tour his museum, which attracted over 3,000 visitors before his untimely death in 1853.