MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

A possible fossilized feather mark in a dinosaur footprint trackway. This fossil is at the Beneski Museum of Natural History, Amherst College. Image courtesy of Ed Gregory Archive.

Edward Hitchcock continued to study footprints over the following years, slowly building his case. He gathered thousands of specimens from over a dozen major locations in Massachusetts and Connecticut. In 1840, a committee from the Association of American Geologists visited Hitchcock's sites and in 1841 issued a report stating conclusively that the impressions were indeed footprints. Fossil footprints were turning up in Britain and on the European continent, too.

Study of the tracks intensified during the 1840s and 1850s. As their familiarity with footmarks deepened, Hitchcock, Deane, Marsh, and others began to question whether all of them had been made by birds. Perhaps some had been made by reptiles? Some of the footprints were shaped like reptile tracks, and it was clear that there were distinct forefeet and hind feet. Had there been four-footed birds? In addition, the men occasionally noticed what they thought could be tail drag marks and impressions of scales in some tracks.

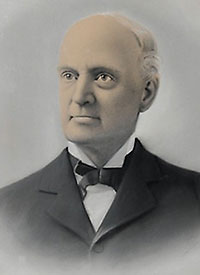

When Dexter Marsh died in 1853, his fossil trade was taken over by Roswell Field, who owned some land where Marsh had excavated. Field's quarries at Gill were considered by Hitchcock to be among the richest in the valley. Field had an orchard and ran several small businesses from his farm. He was not a learned man, but he was a sharp observer, and as had happened for Marsh, fossils opened new worlds for him, both at his feet and in the higher strata of educated society.

With a rich lode to observe on his property, Roswell Field formed some of his own ideas about the fossil footprints. In 1859, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) held its 13th Annual Meeting in Springfield, Massachusetts. Edward Hitchcock hosted the week-long event, but it was the farmer-businessman Roswell Field who made the most interesting announcement about fossil footprints: he declared that none were ever made by birds. All had been made by reptiles. He did not use the new word dinosaur, but this was a hint that the footprints could be related to the odd bones discovered in Britain and Europe.

Three months after the AAAS meeting, Charles Darwin's Origin of Species was published in England, influencing how skeletons and other fossil evidence were interpreted forever after.

Roswell Field

Roswell Field

Ebenezer Emmons Letter to Edward Hitchcock, July 22, 1840

Ebenezer Emmons Letter to Edward Hitchcock, July 22, 1840

Fossil with Many Tracks and Outlines

Fossil with Many Tracks and Outlines

Fossil Showing Multiple Species Tracks

Fossil Showing Multiple Species Tracks

Fossil Showing Feathers and Scales

Fossil Showing Feathers and Scales

The Springfield Republican Reports on Roswell Field's Announcement

The Springfield Republican Reports on Roswell Field's Announcement

Edward Hitchcock's Letter to the Springfield Republican Newspaper, May 14, 1859

Edward Hitchcock's Letter to the Springfield Republican Newspaper, May 14, 1859

American Association for the Advancement of Science

American Association for the Advancement of Science