MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

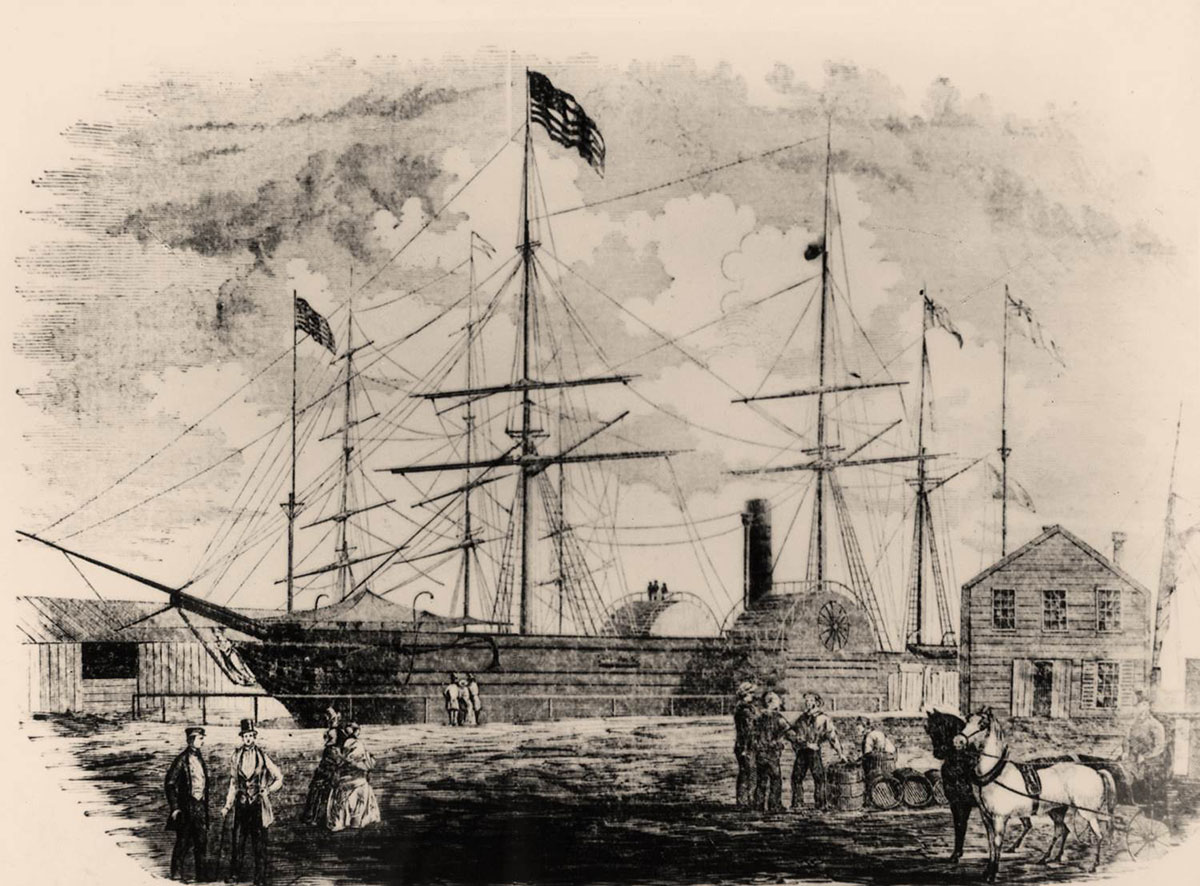

Image of the steamship Canada that took Orra, Edward, and the Tappans to Liverpool. Edward suffered seasickness so badly that they all dreaded the journey home on the America, the Canada's nearly identical sister ship. Image courtesy of Cunard North America.

After he had guided Amherst College away from bankruptcy, Edward requested more than once to be relieved of his presidential duties, but the trustees thought the college still needed him in that role. They acknowledged that it had been a trying period. The school's escape from bankruptcy had exacted a price in the form of significant pay cuts for president, faculty, and staff. In addition, three members of the tiny faculty had died within a few years, and a student as well. President Hitchcock needed a break. What better reward than to send him on a trip to Europe?

Edward had hoped to visit England years earlier to meet John Pye Smith, whose religious and geological views agreed with his own, but that opportunity was lost when he became president. Now, so many years later, he and Orra did not especially want to go, but feeling obliged, they reluctantly packed and made their way to Boston. A trustee, John Tappan, paid for their trans-Atlantic tickets, and he and his wife accompanied the Hitchcocks for much of the trip. They boarded the steamship Canada on May 15, 1850, a rainy day. Orra wept to leave family and friends. Once the ship left the protected bay, she and Edward became seasick and stayed in their “cell,” as she called their room, where “truly a captive did I feel myself to be.”

It stormed all the first night. They lay awake a long while, finally drifting off to sleep and leaving their safety in God's hands. In the morning, Orra heard the sailors singing as they raised the sails. “This comforted me a little for I thought if we were actually perishing they would not sing.” Edward was unwell for the entire crossing, but Orra was soon up on deck to enjoy the sights until the open sea became monotonous. The first thing they did upon landing in Liverpool, after a nap and dinner, was to go to church. "I felt that ever I had cause for gratitude & thanksgiving to God it was then," Orra wrote in her diary.

The next day, Edward bought an aneroid barometer and they left for Chester, an ancient walled English city near the Welsh border, founded by Romans. They traveled the 20 miles in first class, but frugal habits took over and they went second class ("very good") to Bangor, Wales. The breathtaking scenery had a familiar feel, as it reminded them of the mountains of New Hampshire. Edward noted the copper, lead, and coal mines along the way, and the types of flowers, some like the ones at home and others different. He noted that limestone prevailed, with "no bowlders of any size, or any marks of drift agency," and the mountains were treeless.

While Orra and Mrs. Tappan happily spent the days taking it easy and doing a little shopping, the frail Edward ascended Mount Snowdon on horseback, taking advantage of his first chance to use the new barometer. Although rarely mentioned in his notes, it seems that he was with a guide. He found seashells on the summit, indicating that what was now a mountain had been formed at the bottom of a sea. He was intrigued by evidence of glacial action. After a few days of observation, he became certain that enormous glaciers had once descended the mountain peaks of Wales and scoured the valleys smooth (noted also by Louis Agassiz a few years earlier). He later passed the information on to the head of the region's geological survey.

From Caernarvon to Llanberis, he saw traces of ancient beaches 300 to 400 feet above sea level. North of their inn at Llanberis, he examined slate quarries and, unlike at Bangor, noticed "bowlders" and striae indicative of "drift agency." He surmised that the way the layers of rock were bent into an arc was a result of the weight of a glacier. At the top of Mount Snowdon, he saw "shingle & sand several feet thick," which could have indicated old caves and bays of an ocean, but Edward mused that, alternatively, the phenomena may have been the effects of rain. One cloudy day, he experienced the sublime: the clouds lifted, showing a lake and a valley for just a moment, "as if by magic & then they were hidden again." The distances were not as great as in views he had seen in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, but at exotic Mount Snowdon they were a special thrill for the novice American traveler.

Listen to what Orra wrote in her travel diary