MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

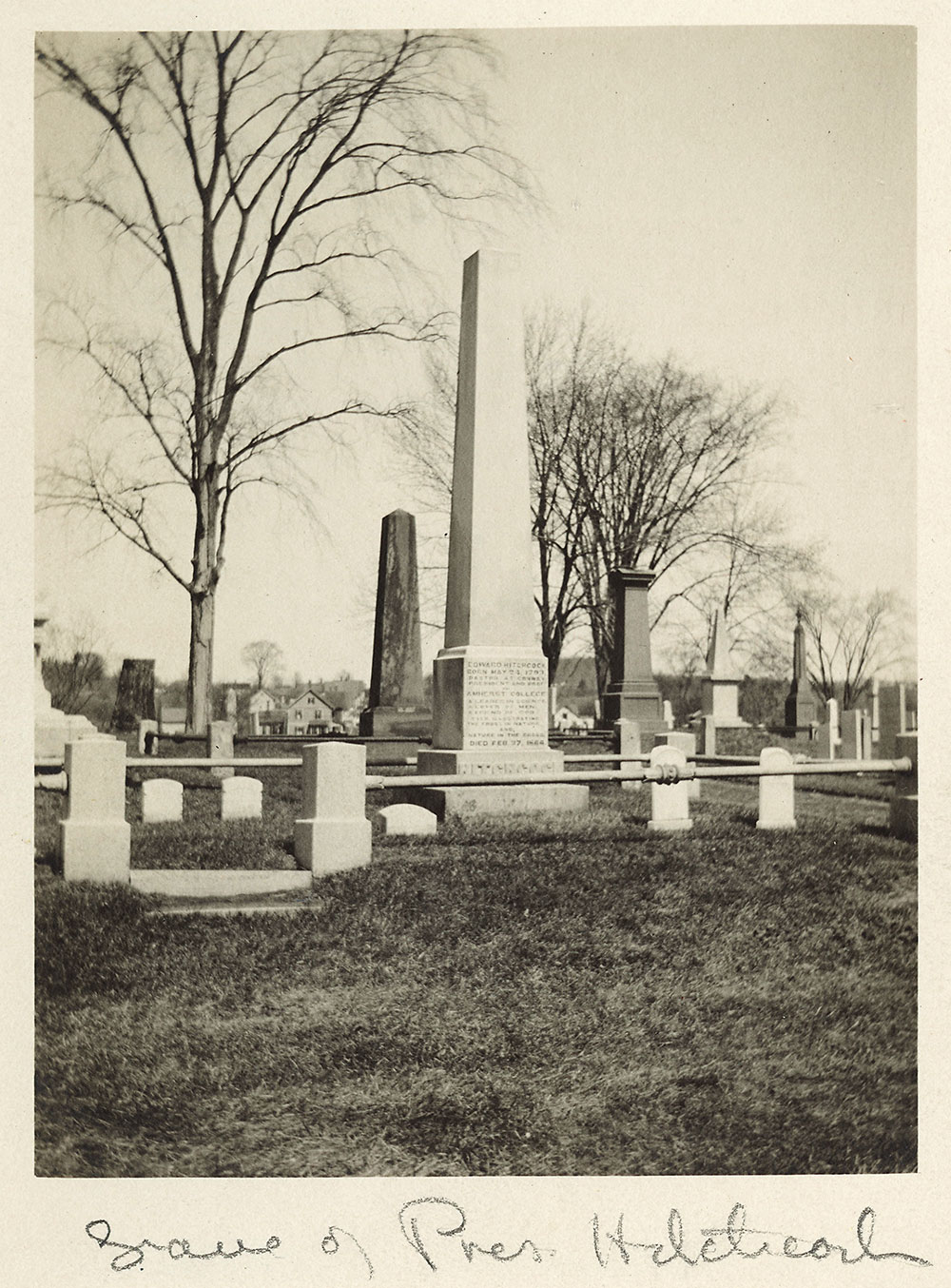

The Hitchcock family obelisk was a change from the religious iconography of earlier New England gravestones. Two small headstones on the left remember baby Edward and an infant who died unnamed. Image courtesy of Edward and Orra White Hitchcock Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

With relief, Edward and Orra moved back into their own home. Edward had his octagonal study connected to the main house and moved the books to where he could easily get to them. Orra arranged the house back to her liking and gladly returned to her garden. Mary, Jane, and Charles (now a student at the college) lived with their parents, but Edward, Jr., and Catharine had married, and Emily was studying in eastern Massachusetts. They were home, but things had changed.

Soon, Edward was back on the lyceum circuit: a letter from February of 1855 described a dreadful trip to West Virginia and Ohio. In January of 1856, he wrote from Chicago about seeing prairies for the first time "as broad as the eye can take in" on a train ride as unsteady as the ocean crossing. He would stop in "Milwaukie" and meet up with Orra in Cincinnati, where daughter Catharine lived, for the ride home. Interestingly, the lifelong teetotaler said that his hosts in Chicago gave him "a glass of good Madiera" that made him sleep well and feel better the next day.

Orra was badly hurt from a fall off a veranda in Amherst in 1855. Although she never recovered fully, this did not stop her from taking a trip to Ohio and later traveling to Montreal and through New England and eastern New York. She may have slowed down by 1860: solicitous as ever, Edward gave her a special chair on New Year's Day.

Edward's mind remained sharp to the end. He published a Smithsonian article on surface geology in 1857. With son Charles, he conducted the official geological survey of Vermont from 1856 to 1861, and in 1858 examined a copper mine in New Jersey. Charles increasingly assisted his father with work on the fossil footprints. The elder Edward contributed to Elementary Anatomy & Physiology by son Edward, now a physician, who also took over his father's habit of clearing pathways up local hills and orchestrating elaborate public renaming ceremonies for them.

Edward continually revised his writings: a second edition of Religion of Geology and a third edition of Phenomena of the Seasons in 1859 alone, the same year he defended himself against James Deane's claim to discovery of fossil footprints. He made multiple revisions to Elementary Geology. This book contained what is recognized as possibly the first "tree of life" paleontological chart, drawn by Orra. After the publication of Charles Darwin's Origin of Species in November, Hitchcock discontinued the chart, fearing that it inadvertently gave support to evolutionary ideas.

Characteristically, Edward did not give up teaching, even when he finally had to have students come to his sickbed. He occasionally heard from former students and sent back astute replies. In 1862, he completed Reminiscences of Amherst College. One of his last acts outside the home was to appeal to the state legislature in April of 1863, for a $25,000 grant to the college natural history department.

Orra died first, on May 26, 1863, just days before their 42nd wedding anniversary, despite a lifetime of expectation that Edward would precede her. He died nine months later, on February 27, 1864. Both deaths were surrounded by family and followed by public mourning in Amherst, heavily attended by the town as well as the college to which they had devoted their very full, very active, extraordinarily productive lives.

Edward Hitchcock's Letter to Orra White Hitchcock, January 2, 1856

Edward Hitchcock's Letter to Orra White Hitchcock, January 2, 1856

The Religion of Geology, Edward Hitchcock

The Religion of Geology, Edward Hitchcock

Orra White Hitchcock's Letter to Eunice Huntington, February 11, 1856

Orra White Hitchcock's Letter to Eunice Huntington, February 11, 1856

Vermont Geological Survey, Edward Hichcock

Vermont Geological Survey, Edward Hichcock

Edward Hitchcock's Paleontological Chart Drawn by Orra White Hitchcock

Edward Hitchcock's Paleontological Chart Drawn by Orra White Hitchcock

Ichnology of New England, Edward Hitchcock

Ichnology of New England, Edward Hitchcock

Agricultural School Report, Edward Hitchcock

Agricultural School Report, Edward Hitchcock

Orra White Hitchcock's Letter to the Children, August 23, 1850

Orra White Hitchcock's Letter to the Children, August 23, 1850

Tribute to Orra White Hitchcock, William Seymour Tyler

Tribute to Orra White Hitchcock, William Seymour Tyler

The Religion of Geology

The Religion of Geology