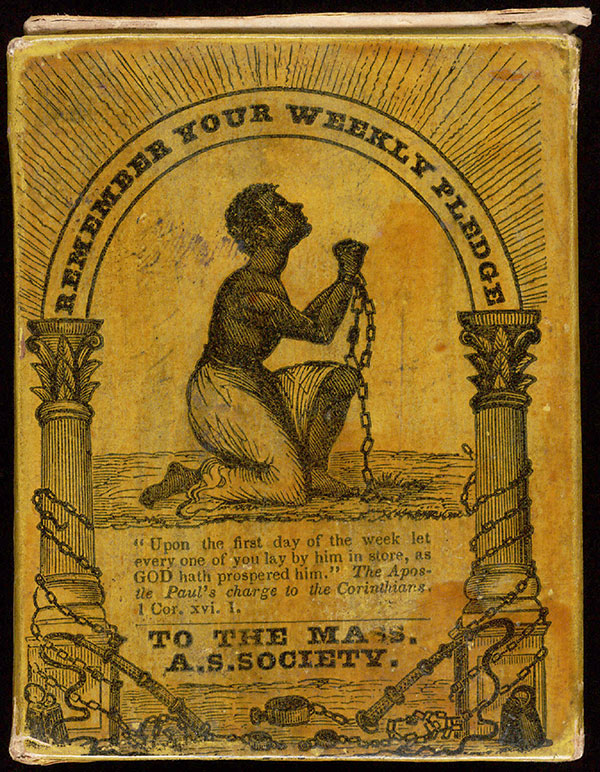

Slavery had been effectively banned in Massachusetts since 1783, but Hitchcock's parents must have remembered slaves in Deerfield homes. Image courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Bitter sectional debates and controversies over slavery in the decades before the Civil War pitted northern states against southern. As Congressmen and citizens focused on the divisions between the slave-holding South and a free North, few acknowledged that until recently, slavery had been part of the social, economic and political landscape of the entire nation, including Massachusetts and the other New England states.

Massachusetts was the first colony in Britain’s mainland North American possessions to legalize slavery, writing it into the Body of Liberties in 1641. Enslaved African and Native men, women, and children became part of a brisk trade with the West Indies, where international markets in sugar and rum connected all of the colonies to a thriving transatlantic economy that supplied the public's exponentially growing demand for sugar's addictive sweetness. The trade caused incalculable misery for millions of enslaved Africans forcibly transported to the Americas to grow, harvest and process it.

The American Revolution’s emphasis on freedom and natural rights put slavery on the defensive in a way it had not been before. Massachusetts never formally abolished it, but a number of high-profile court decisions made clear that the law would not assist slave owners in retaining their human property. Other northern states adopted laws freeing enslaved people born after a certain date and after serving for a specified term, but this manumission process favored owners by being both limited and very slow. Although the number of enslaved people in New England was never as high as in southern states or the West Indies and South America, slavery persisted in New England long after the Revolution. As a result, there were slaves in “free” states like Connecticut and Rhode Island well into the 1840s.

Meanwhile, the framers of the new federal Constitution included a clause outlawing the importation of slaves into the United States after 1808. Anti-slavery societies appeared throughout the new states and, for a time, it seemed to some optimistic observers in the 1780s and ‘90s that slavery was on the way out. Their confidence was misplaced, mainly because they had not anticipated the Industrial Revolution of the early 1800s. The invention of the cotton gin in 1792, made slavery more profitable than ever as southern planters were able to process enormous quantities of raw cotton that new factories in Britain and northern states were eager to buy and manufacture into finished textiles. Owners of large southern plantations became the wealthiest Americans in the nation, and many northern mill owners joined the ranks of the elite. Rather than disappearing, slavery in the United States seemed more entrenched than ever.

Still, the economic and political sway of pro-slavery elements could not stave off the growing anti-slavery movement in the northern states. Although radical abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison, demanding the immediate abolition of slavery, were feared and often persecuted, more and more men and women throughout New England condemned slavery on both moral and religious principles. The separation of enslaved families--husbands from wives, mothers from children--was of special concern, as were reports of other sorts of brutal and inhumane treatment disseminated through Garrison's abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, and other publications. The image of a male or female slave in chains, arms raised in supplication appeared in prints, medals, and ceramics, reminding viewers of the daily evils of chattel slavery.

By the 1830s, western Massachusetts was the epicenter of the state’s growing anti-slavery movement. Numerous towns in Franklin County founded anti-slavery societies, verifying the abolitionist Theodore Weld's claim that "The springs [of the anti-slavery movement] lie in the country." Women, including those of color, proved particularly active, forming in Garrison's words, a "great army of silent workers" who wrote and shared anti-slavery literature, sponsored lecturers, circulated petitions, offered assistance to African Americans escaping slavery, and raised funds for the cause.

The slavery question could unite or divide people in their public as well as personal lives. College students and faculty at Amherst College and other northern schools hotly debated the issue. Many southern students enrolled there returned home or sought out southern institutions to continue their education when war became likely. On the other hand, the men vying against one another in the controversy over who should receive credit for the discovery of fossil footprints found common ground in antislavery. Their varying stances and activities, however, also reflected how New Englanders opposed slavery in different ways. Benjamin Silliman of Connecticut had been raised in a slave-holding family, but as an adult supported the Colonization movement that called for the "return" of African Americans to Africa.

Edward Hitchcock and his wife Orra were typical of many people in western Massachusetts in opposing slavery while distancing themselves from William Garrison's demands for immediate abolition. Dexter Marsh's father was far more radical and well known locally as an abolitionist; Dexter himself may have been active in the Underground Railroad. Like most northerners, Dr. James Deane opposed slavery's expansion into newly admitted states, and even was a delegate to the Free Soil convention. His eulogist and champion, Dr. Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, was a radical abolitionist in Boston. He co-founded the Anti-Man-Hunting League, a secret organization devoted to resisting the recapture of escaped slaves under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The issue of slavery would increasingly overshadow personal and professional relationships as tensions escalated and the country careened toward open conflict and civil war.