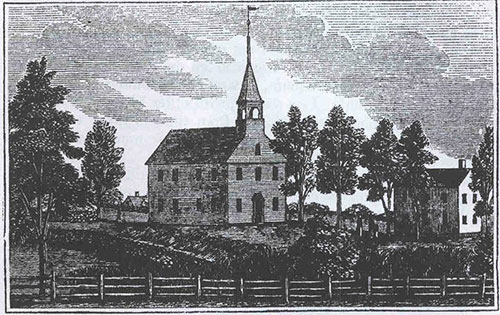

Image courtesy of Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library.

New Englanders' religious beliefs and practices changed dramatically between the 17th and 19th centuries. The newly fashionable Greek Revival meetinghouses of the early 1800s, complete with white clapboards and tall steeples, symbolized these changes and the cultural shifts that accompanied them.

The American Revolution's celebration of individual freedoms and representative government challenged the notion of a single, state-supported religion. In the same period, increasing numbers of men and women grew convinced that they could open themselves to salvation through their own efforts. By turning to free will, or Arminian theology, they rejected the pessimistic doctrine of total and helpless depravity that defined orthodox Calvinism. Optimism about humankind's ability to improve itself and the world lay at the heart of the explosion of religious revivalism at the turn of the 19th century that historians refer to as "The Second Great Awakening".

Descended from the old Puritan order, Congregational churches had maintained their privileged tax-supported status in every New England state except Rhode Island. This did not mean these congregations and communities were immune from the religious and social upheavals of the era. This was in part due to the theological battle lines being drawn in New England’s colleges, where ministers were traditionally educated. Yale’s curriculum and faculty remained committed to Calvinism and new schools like Middlebury and Amherst Colleges were adamantly orthodox. The appointment of Edward Hitchcock, an orthodox Congregational minister, as president of Amherst College in 1845, both confirmed and solidified the college's reputation as a bastion of conservative Protestantism.

Harvard College, however, was another story. Long considered the traditional intellectual and theological training ground for Congregational ministers since its founding, Harvard shocked the nation in 1806, by bestowing its prestigious Chair of Divinity upon the Reverend Henry Ware. In a complete departure from orthodox Congregationalism, Ware embraced Unitarianism, rejecting the doctrine of the Trinity (God as Father, Son and the Holy Spirit) in favor of a single divine entity. Ware and other influential liberal Protestant ministers, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and William Ellery Channing, cast God and His creation in new terms that emphasized harmony, spiritual equality, and a relationship based not on fear and coercion but love and affection.

Congregational churches and colleges split over what was fast becoming the theological and social question of the hour. Should churches and clergy adhere to the old Calvinist orthodoxy that assumed the innate depravity and likely damnation of all but a few people chosen by God before they were born? Or, should they join the Unitarians and embrace an optimistic theology in which salvation was within reach of all who genuinely repented of their sins?

The debate between orthodox Calvinism and Unitarianism came early to Deerfield, Massachusetts. In 1807, church members voted to hire the Reverend Samuel Willard, a recent graduate of Harvard and a strong Unitarian. When a council composed of ministers from neighboring towns refused to ordain Willard, the Deerfield congregation, including Edward Hitchcock's father and other orthodox members, stood behind their new minister. Other members left the church and joined orthodox parishes in nearby towns; they would eventually establish a new orthodox Congregational Church in South Deerfield in 1818 and one in Deerfield in 1838.

Although the Congregational/Unitarian controversy loomed large in New England communities like Deerfield, relatively few Americans embraced Unitarianism. Most, instead, turned to some form of evangelical Protestantism in a massive religious revival dominated by Methodists and Baptists. Charles Grandison Finney (1792-1875) was a lawyer and a religious skeptic before a conversion experience turned him into an ardent Methodist and one of the greatest evangelical revival preachers in American history. "The Great Itinerant" attracted huge crowds, converting an estimated 500,000 people through his ministry.

The intense and sometimes disorderly aspects of revival meetings associated with the Second Great Awakening concerned Unitarian as well as Congregational, Presbyterian, and Episcopalian Church leaders. Finney’s preaching exemplified the Second Great Awakening's emphasis on the ability of people to change their hearts and prepare themselves to experience salvation. In the process, his message undermined the orthodox state-supported Congregational church. The Reverend Lyman Beecher accused Finney of planning to "come into Connecticut and carry a streak of fire all the way to Boston." Beecher promised Finney, "as the Lord liveth, I'll meet you at the State line, and call out all the artillerymen, and fight every inch of the way to Boston, and then I'll fight you there." Beecher later reflected, however, that disestablishing the Congregational church in 1818, "was the best thing that ever happened to the state of Connecticut. It cut the churches loose from dependence on state support. It threw them wholly on their own resources and on God."

Perhaps the most significant effect of the Second Great Awakening was the way in which it helped Americans to connect with one another in an expanding and mobile society. Men and women founded countless reform associations to put into practice the optimistic, evangelical message of the Awakening. Revivalism also inspired utopian societies whose members sought to perfect the world through reforming living arrangements, diet, and sexual practices.