MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

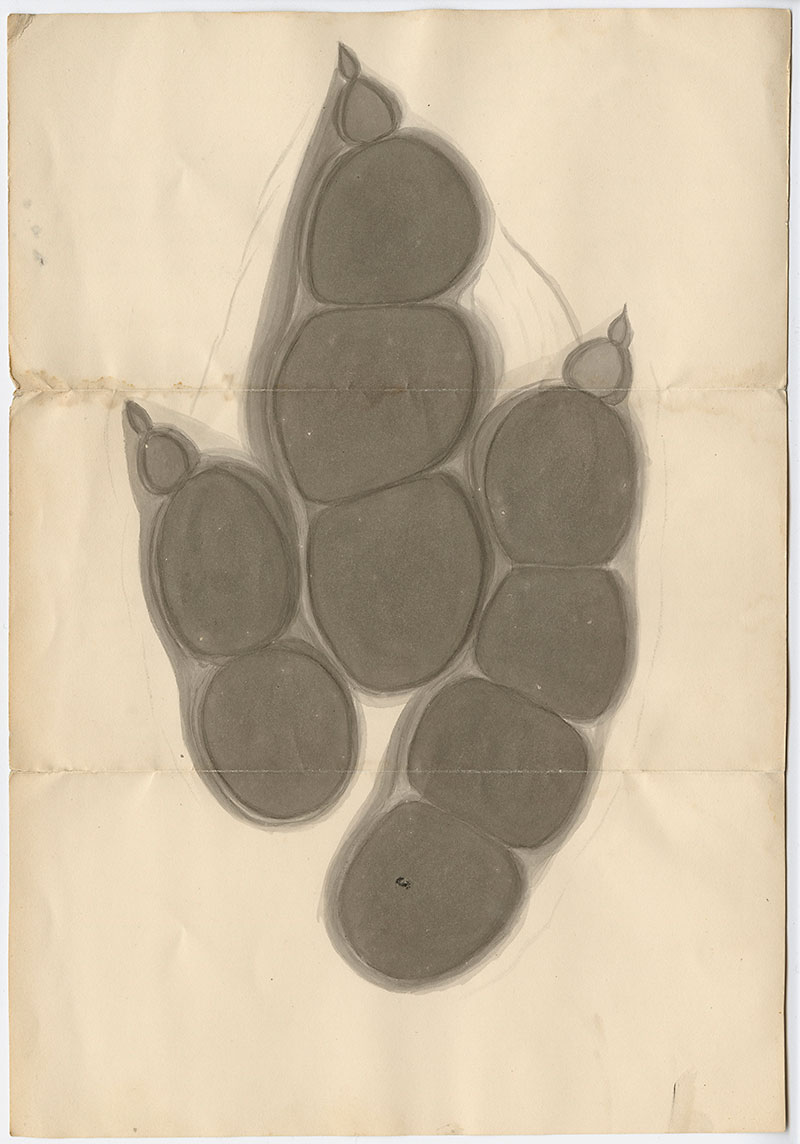

The drawing that James Deane made to accompany his letter to Edward Hitchcock. Image courtesy of Edward and Orra White Hitchcock Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

Benjamin Silliman and Edward Hitchcock were excellent choices, as they were among the most influential men in American science. Silliman was the founding editor of the American Journal of Science, the most important scientific publication in the country at the time. Hitchcock not only taught sciences at Amherst College, but also was Massachusetts’ official state geologist and had done the state's first geological survey just a few years before. They treated Dr. Deane’s letters with respect—but they did not think he had found fossilized bird footprints.

Hitchcock wrote back to Deane that the marks might have been made by a geological process, such as erosion, rather than by a living creature. He had seen similar marks in red sandstone, he said, and understood why Deane thought they had been made by a bird, but it was very unlikely. He was interested in seeing the impressions, though, so he asked Deane to set the specimens aside.

Deane thought that the resemblance to bird tracks was too close to be coincidental. Undeterred, he wrote another letter attempting to convince Hitchcock of his ideas. When he received no reply, too excited and impatient to wait any longer, he sent another letter to both men, this time accompanied by plaster casts and drawings.