"Historical Collections, being a General Collection of Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes &c.", John Warner Barber. Image courtesy of Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library.

Hundreds of private academies sprang up in the decades following the American Revolution. Unlike the grammar schools and private tutoring of an elite few bound for college, these academies opened their doors to anyone who could afford their relatively modest fees. Their existence testified to the belief that only educated men and women could sustain a free republic. In the process, they educated a rising generation of Americans for a wide range of occupations. At the same time, educators and writers identified important differences between men and women and the spheres they occupied. A gender-based vision of what constituted proper education for men and women grew out of this notion of separate spheres.

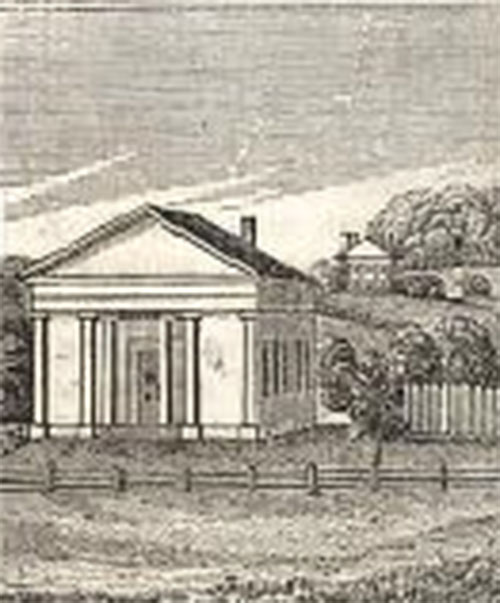

Academies generally were established in larger towns or village commercial centers, but drew students from a broad geographic area. Litchfield Academy, also known as Miss Pierce’s School, for its founder, Sarah Pierce, opened in 1792, and attracted students from other states and even as far as the West Indies. When plans were laid to establish an academy at Deerfield in the 1790's, proponents of what would become Deerfield Academy sought out students not just from Deerfield but the surrounding region. Often housed in impressive two-story buildings, academies symbolized a commitment to education and, by extension, demonstrated a community’s refinement and cosmopolitanism.

The academy building in Deerfield was designed by the architect Asher Benjamin and was, in the words of its first Preceptor, “an elegant Edifice, having, on the lower floor, four rooms, one for the English school, one for the Latin, & Greek school, the Preceptor's room, and a room for the Museum and Library. The upper room, being all in one, is used for examinations, and exhibitions.”

Many academies were single-sex, but a number, like Deerfield Academy, were co-educational from the start. This did not mean that boys and girls followed the same course. Young men were expected to receive instruction in subjects beyond the basic literacy taught in the common schools (similar to today's elementary schools). For some, a term or two at the academy was the end of their formal education; for others, it was important preparation for passing college entrance exams and a college-level course of study. Male students typically took courses in Latin, Greek, mathematics, English grammar, writing, literature, penmanship, and rhetoric. Later additions to the curriculum included geology, astronomy, and natural history. At Deerfield Academy, a cabinet, or museum, of shells, minerals and other objects engaged and instructed students in natural history, and a benefactor donated funds to purchase the latest top-of-the line equipment from London to teach astronomy.

Academy education was especially important for women, as it represented one of the only options for formal education beyond rudimentary instruction in a common school setting. Almost 400 female academies, also referred to as seminaries, opened between 1790 and 1840. To prepare young women to fulfill their primary role as wives and mothers in the new republic was the main goal of female education in this period. John Gardiner, an Episcopal minister, expressed this view when he declared that women were "the first and most important guardians and instructors of the rising generation." In addition to grammar, arithmetic, and history, academies offered instruction in female "accomplishments" such as drawing, cartography, embroidery, painting and music. These productions simultaneously displayed a young woman’s refinement, artistic skills and intellectual attainments.

Epaphras Hoyt of Deerfield observed first-hand the life-changing potential of an academy education. His nephew, Edward, was a bookish boy with a keen intellect who had no interest in being either a farmer or following his father, Justin, into the hat-making or other artisanal trade. Justin sent Edward to Deerfield Academy, where he thrived. Edward himself became a teacher at the school, and despite never receiving a college degree, went on to become a respected clergyman, a professor, a celebrated geologist, and the president of Amherst College. He met his wife-to-be, Orra White, when she was also teaching at the Academy.

In an address he delivered in 1839, Epaphras Hoyt mused on the changes in education for boys and girls that took place after the Revolution. As an amateur scientist and early mentor to Edward, Hoyt was particularly struck by the progress and contributions of women working and teaching in the sciences. Epaphras may have been thinking of his nephew’s intellectually gifted wife, Orra White Hitchcock, when he declared, “At this day [1839] no inconsiderable number of the sex have attained a high niche in the temple of science.”

At such demonstrations of intellectual ability, Hoyt acknowledged that “female talent with due cultivation is in no respect deficient!” Perhaps thinking of his own mother, wife and sisters, who had received little formal education, he insisted that women of the previous generation “were by no means deficient in the useful branches; and many such mothers were justly the pride of their children.” But, Hoyt also asked his audience to consider the implications of women capable of demonstrating their intellectual capacity.

are they not as some ascertain, entitled to the same rights and privileges, as they are called, of males? When I examine the principles of equality as laid down in our Constitution, I confess, nothing appears against the correctness of this position. In Europe we see females may be Queens at 19 years, and wield the executive power of great nations; and if Queens, why not members of parliament and entitled to all offices confirmed on our Sex!

Hoyt, however, agreed with most of his contemporaries that a fully co-educational classroom for young men and women could not transcend the essential differences and mutual attraction between the sexes, saying ruefully, “Should such a system be adopted, a difference made of education might be necessary for them; and on our[s] spent a deeper logic, to counteract the effect of female anatomy, when displayed in the fascinating charms of the sex.”

Epaphras Hoyt’s ambivalence reflected a concern among some that academy education would result in young women being dissatisfied with the roles of wife and mother to which society assigned them. A comical sketch at one school poked fun at the stereotype through one character who had no interest in attending an academy. After all, she said, “Uncle Tristam says he hates to have girls go to school, it makes them so dam’d uppish & so deuced proud that they won’t work . . . How will the young fellows take it if we shine away & don’t like their humdrum ways—Won’t they be as mad as vengeance—& associate with the girls that don’t go to school?” (from the 1799 unpublished diary of Sally Ripley, American Antiquarian Society)

Belying the cultural ambivalence about the potential for academy education to create a cadre of snobbish graduates, academies were a crucial resource for educating the children of ordinary farmers, mechanics and artisans. Students might attend only a quarter or two and then perhaps teach a common school term to earn more money to come back for another term. By providing an inexpensive course of study in a wide range of subjects, academies created new pathways of mobility for young people eager to strike out on their own beyond the villages of their parents. The heterogeneous enrollment at many schools introduced students to a wider acquaintance and accompanying lifelong associations.