MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

"The Oxbow of the Connecticut River", Unknown, after William Henry Bartlett, AC1948.54 Image courtesy of Mead Art Museum, Amherst College.

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “A Psalm of Life” 1838

In the fall of 1841, Bostonians flocked to hear Charles Lyell, the famous British geologist, lecture on the latest geological theories and discoveries. Margaret Fuller’s review of Lyell’s Boston lectures revealed how fossil enthusiasts and early geologists had captured the attention of ordinary men and women on both sides of the Atlantic. Fuller, the editor and tireless contributor to the Transcendentalist magazine, The Dial, reported that a “very large audience" showed “uniform attention and warm interest in [the] lectures of this celebrated geologist.” She noted that while Lyell clearly lacked experience speaking to non-specialists, his "extensive knowledge, patience, and philosophical habits of investigation, with his simple and earnest manner of approaching his subject made his lectures not only interesting but charming to his audience.” Fuller also observed that Lyell’s impact persisted after the lecture series had ended. “Wherever we went, there was Lyell’s [Principles of] Geology on the table, and many of the suggestions made by these lectures lingered in conversation through the winter.”

Throughout the 1830s and 40's, geological findings and interpretations produced impressions on the culture as indelible as the fossil footprints embedded in the rocks of New England’s Connecticut River Valley. Decades before Charles Darwin published his work on the origin of species and natural selection, popular literature, lyceum lectures, educational works for children, and even novels testified to the spreading influence of a new science that challenged and even upended long-standing assumptions about the Earth’s ancient past and that of its inhabitants, past and present.

“Amidst the din of rushing [river] waters the noise from the stones, as they rattled one

Charles Darwin, Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of H. M. Ships Adventure and Beagle, 1839

over another, was most distinctly audible even at a distance...The sound spoke

eloquently to the Geologist...it is like thinking of time, where the minute that now glides

past is irrecoverable. So it is with these stones; the ocean is their eternity, and each note

of that wild music tells of one other step towards their destiny.”Listen! you hear the grating roar

Matthew Arnold, “Dover Beach,” 1867

Of pebbles with the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

As Margaret Fuller observed, Charles Lyell’s three-volume Principles of Geology, published in 1830-33, graced many a parlor table and bookshelf on both sides of the Atlantic. Lyell’s emphasis on the Earth’s extreme age was a centerpiece of his writing and lectures. His compelling description of the inexorable geological processes that erected and leveled mountains, unleashed cataracts and extinguished mighty rivers over millions of years opened for his audiences a deep, almost unfathomable past. In the process, Lyell and other geologists introduced an alternate narrative to traditional, biblically determined chronologies of the Earth’s origins and history. Instead of an anthropocentric vision of the creation of the Earth and human beings in historical time, people for the first time encountered the revelations of deep time encompassing hundreds of millions of years.

By 1833, people could visit the fossil museum Gideon Mantell opened in his home in Brighton, England. The museum's curator, George F. Richardson, captured the sense of wonder of seeing these fossils in his poem, “Visits to the Mantellian Museum”:

Tis indeed a world of wonder,

Found within the earth and under;

Fancied forms and wild chimeras

Creatures of primeval aeras,

Startling all our ancient notions,

Showing lands of old were oceans;

Showing oceans once were dry,

As the mountains old and high!

Mantell’s museum inspired yet another poet, Horatio Smith (1779-1840). He was known for waggish, good-natured mimicry of the most popular Romantic poets of the day. His humorous poem, “A New Nightmare,” teased readers in 1838 with the fancied effect on a man who fell asleep among Dr. Mantell’s geological and paleontological specimens, including the enormous, toothy creatures Mantell christened the iguanodon:

In the midst of these relics, o’ertaken by sleep,

A dream whisked me away suddenly back at a leap

To the great geologic eras

When before me arose, in apocalyptic din,

Realities far more terrific and grim

Than the wildest of fabled chimeras

Like Richards' "Visits to the Mantellian Museum," Smith’s poem captured the awe and wonder these discoveries and accompanying new interpretations evoked. But, his dream also revealed deep-seated fears of a frightening primordial world inhabited by “monsters”:

Oh, what was my fright when all turned upon me,

Each growling with looks of infuriate glee

“Yours, yours are the culpable shoulders

That bore off our bones from the quarries, to raise

Amazement and fear, when exposed to the gaze

Of featherless biped beholders!

"A New Nightmare" suggests how geologists of the early 1800s cut men, women and children adrift from a human-centered universe, replacing it in the process with an indifferent cosmos populated by strange and often frightening species. Many found this new science unsettling, to say the least, and a number of poets captured the emotional vertigo it unleashed. The amateur geologist and fossil seeker, Constantine Rafinesque, acknowledged the deep mysteries of geological time in a poem he wrote in 1836, cautioning against "theories and speculations wild…To man it was not giv’n to know the whole, Dark mysteries of generations past."

Alfred Tennyson, one of the most universally beloved poets of the Victorian era, explored both geological and emotional landscapes in a tribute to his deceased and deeply mourned friend, Arthur Hallam. Composed over a number of years during the 1830s and '40s, “In Memoriam” acknowledged geologists who spoke of an Earth hundreds of millions of years in the making:

They say

The solid earth whereon we tread

In tracts of fluent heat began

And grew to seeming-random forms,

The seeming prey of cyclic storms,

Till at the last arose the man

* * *

There rolls the deep where grew the tree.

O Earth, what changes hast thou seen!

There where the long street roars, hath been,

The stillness of the central sea.

Tennyson struggled to reconcile discrepancies between the biblical narrative of creation and impersonal, inexorable, geologically determined processes:

Are God and Nature then at strife,

That Nature lends such evil dreams?

So careful of the type she seems,

So careless of the single life;

Even as the new geology shook the historical scaffolding of his belief, Tennyson clung to his faith in God:

I stretch lame hands of faith, and grope,

And gather dust and chaff, and call

To what I feel is Lord of all,

And faintly trust the larger hope.

Tennyson was not the only literary figure grappling with geology and faith. In 1851, the English art critic and social commentator, John Ruskin, confessed to his friend Dr. Henry Acland, “If only the Geologists would let me alone, I could do very well but those dreadful hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verse.” Far away in Amherst, Massachusetts, Emily Dickinson confronted the same dilemma in her poem, “The World is not Conclusion”:

Faith slips - and laughs, and rallies -

Blushes, if any see -

Plucks at a twig of Evidence -

And asks a Vane, the way -

Much Gesture, from the Pulpit -

Strong Hallelujahs roll -

Narcotics cannot still the Tooth

That nibbles at the soul

Dickinson’s reference to a fossil tooth reminded readers that she grew up across the street from Amherst College where Edward Hitchcock taught geology. Dickinson attended lectures by Hitchcock as a student at Mary Lyon’s Seminary (later Mount Holyoke College) but, unlike Hitchcock, she confronted head-on the metaphysical implications of fossil footprints and teeth from long-extinct creatures.

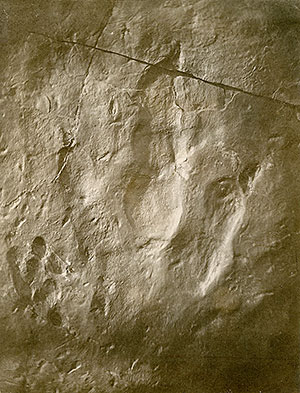

Even as Tennyson, Dickinson and other contemporaries grappled with reconciling science and faith, fossil footprints in the Connecticut River Valley, lithic remains like Gideon Mantell’s famous iguanodon in England, and other geological discoveries appeared remarkably quickly in children’s school books and juvenile literature.

The Youth’s Cabinet, published in Boston, was among the first American periodicals to enthusiastically recommend the study of geology for children. In 1841, Josiah Holbrook, one of the early founders of the Lyceum movement, contributed an illustrated article in which he emphatically claimed that geology had “now become almost as common as the elements of geography, and of course it is supposed that every person, even with the most limited education, is familiar with the elements of the science, and with the simple minerals, and families of rocks, which compose our globe.” Some publications now made a point of discounting the catastrophic interpretation of a great deluge from God. In an imaginary dialogue between a parent and his children reprinted in an American periodical in 1843, a father gravely assured his curious offspring, “No one has a greater reverence for that sacred book [the Bible] than I have . . . but I think, that an examination of the different strata, as they are called, proves that he did not.”

Contemporary adult literature likewise revealed the impact of geology and paleontology. Direct references and metaphorical allusions to fossils and fossil imprints appeared with increasing frequency. America’s most popular poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, expressed in 1838, his wistful hope of legacy after death in the famous passage, “We can make our lives sublime/And, departing, leave behind us/Footprints on the sands of time.” Ralph Waldo Emerson used the language of science to describe the origin and function of human communication. “Language,” Emerson declared in 1844, “is fossil poetry. As the limestone of the continent consists of infinite masses of the shells of animalcules, so language is made up of images, or tropes, which now, in their secondary use, have long ceased to remind us of their poetic origin.” Thomas Wentworth Higginson would use the language of fossils when he confided to readers of The Atlantic that the first letter he ever received from Emily Dickinson “was in a handwriting so peculiar that it seemed as if the writer might have taken her first lessons by studying the famous fossil bird-tracks in the museum of that college town [Amherst, Massachusetts].”

Geological terms and assumptions began turning up in works of fiction, simultaneously educating and confirming popular understandings of the science and romanticism of rocks and fossils. Moby Dick is Herman Melville's best known work, but before he introduced Captain Ahab, Ismael and Queequeg to the world, there was Mardi, and a Voyage Hither, published in 1849. In Mardi, characters encounter an “Isle of Fossils,” and wish to know the nature and origin of mysterious tracks in the rock. Melville’s narrator describes the tracks in language reminiscent of those Dexter Marsh had discovered in Greenfield, Massachusetts, only fourteen years earlier: “Upon a long layer of the slaty stone were marks of ripplings of some now waveless sea; mid which were tri-toed footprints of some huge heron, or wading fowl.” When Melville published his masterwork Moby Dick in 1851, he revisited the geology and fossil history of the Earth in a chapter entirely devoted to “The Fossil Whale.” Part science and part metaphysics, Melville asked readers to seek to more completely understand the whale not only in his present habitat, but also to “magnify him in an archaeological, fossiliferous, and antediluvian point of view.”

Twenty years later, in 1873, geological strata and fossils assumed center stage in A Pair of Blue Eyes, a novel by the acclaimed English novelist Thomas Hardy. In an intense, nail-biting scene, Henry Knight, a geologist, clings desperately to the dangerous cliff face where he has fallen, hundreds of feet above the ocean. Hoping against hope for rescue, he faces his own perhaps imminent death as he stares at a fossil in the cliff face:

…opposite Knight's eyes was an imbedded fossil, standing forth in low relief from the rock. It was a creature with eyes. The eyes, dead and turned to stone, were even now regarding him. It was one of the early crustaceans called Trilobites. Separated by millions of years in their lives, Knight and this underling seemed to have met in their death. It was the single instance within reach of his vision of anything that had ever been alive and had had a body to save, as he himself had now.

Even in this moment of crisis, Henry Knight’s calling marshaled his thoughts. “Knight was a geologist; and such is the supremacy of habit over occasion, as a pioneer of the thoughts of men, that at this dreadful juncture his mind found time to take in, by a momentary sweep, the varied scenes that had had their day between this creature's epoch and his own.”

“We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.”

H.P. Lovecraft, 1926

In 1893, Francis Underwood revisited the scenes of his childhood home in his novel Quabbin, a thinly disguised reminiscence of life during the 1830s and '40s in the small western Massachusetts town of Enfield in the Swift River Valley. In one memorable scene, “Mr. Wentworth”, a conscientious, college-educated schoolmaster employed by the local female academy, bemoans to his hostess and other guests at an afternoon tea the lack of knowledge among students of what he considered the most basic facts of geology: "I happened the other day to make a reference to geology, and found they hadn't the least notion of it. For very shame I had to stop and make some explanations upon the structure of the earth's crust."

The schoolmaster's ensuing description of his gentle suggestion to his class “that it wasn't necessary to hold strictly to biblical chronology" as "the testimony of the rocks was evidence which could not be contradicted" satisfied some listeners. It troubled his young hostess, however, who volunteered that, “she had heard a sermon by Professor Hitchcock, the great geologist, and thought he showed there was no conflict between Genesis and geology.” Unwilling to offend or distress her by challenging further Edward Hitchcock’s firm belief in the unity of orthodox religion and science, schoolmaster Wentworth could only respond, "On that subject, I say nothing. For the sake of the book [of Genesis], I hope it is so; science will take care of itself.”

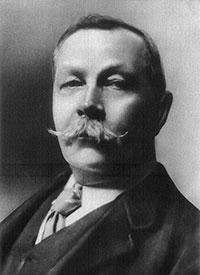

Looking back from the 1890s, Underwood understood that Charles Darwin’s theories of natural selection and evolution would only widen further the gulf between traditional religious narratives of creation and scientific explanations for the fossil record. Undeterred, or perhaps spurred on by cultural ambivalence, subsequent generations of writers continued to explore the implications of a prehistoric world and an ancient cosmos. Many popular authors, including Jules Verne, Edgar Allan Poe, and even Arthur Conan Doyle would springboard from geology into science fiction and fantasy. Remembered today for creating the character of Sherlock Holmes, Doyle tapped into the popular fascination with dinosaurs in his 1912 novel The Lost World, in which the iguanodon and megalosaurus still roamed a remote plateau in the Amazon. Long before Michael Crichton wrote Jurassic Park in 1990, Doyle’s premise proved so compelling it was adapted for the screen in 1925. Edgar Rice Burroughs similarly captivated readers with pterodactyls, allosauruses and woolly rhinoceroses in his 1918 serial, The Land that Time Forgot.

For some, scientific revelations opened doors of terror as well as wonder. In 1926, H.P. Lovecraft cautioned, “We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.” A writer of science fiction horror, Lovecraft blamed new discoveries for taking humans out of their depth. “The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

The discoveries and bold new interpretations by geologists simultaneously founding new fields of science launched a literary fascination with geological time and the Mesozoic era in particular. George F. Richardson’s poetic effusion in 1838, over "Wondrous shapes, and tales terrific/Told in Nature’s hieroglyphic" heralded the beginning of the popular allure of a fossil record whose impression on the culture only continues to deepen.

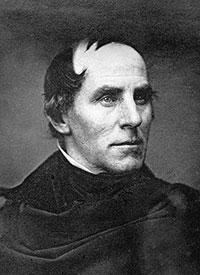

Thomas Cole

Thomas Cole

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson

Arthur Conan Doyle

Arthur Conan Doyle

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson

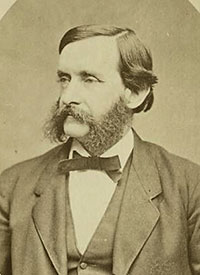

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

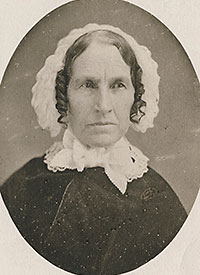

Orra White Hitchcock

Orra White Hitchcock

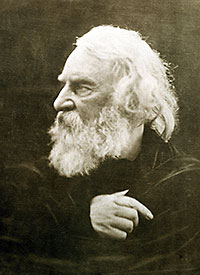

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Charles Willson Peale

Charles Willson Peale

Daniel Wadsworth

Daniel Wadsworth

Geological Poems, American Journal of Science, Vol. V, 1822

Geological Poems, American Journal of Science, Vol. V, 1822

Arthur Conan Doyle's "Lost World"

Arthur Conan Doyle's "Lost World"

Catastrophism and Uniformitarianism

Catastrophism and Uniformitarianism

Emily Dickinson, Geologist & Naturalist

Emily Dickinson, Geologist & Naturalist

The Wadsworth Atheneum

The Wadsworth Atheneum

Photography and Geology

Photography and Geology

Picturesque Aesthetic Theory and the Sublime

Picturesque Aesthetic Theory and the Sublime